Translate this page into:

A Paradigm Shift of Services by Providing Simple Cost Effective Interventions and Future Considerations in Managing the Care of Obese Women in Pregnancy

*Email: bsagoo@doctors.org.uk

Abstract

Objective:

Our study explored a cohort of pregnant women to evaluate clinical care antenatally, at delivery and postpartum. We piloted the use of two simple measures: firstly the use of a patient educational leaflet in improving knowledge of risks associated with obesity during pregnancy and secondly, the use of a proforma to improve documentation in the management of obese women in pregnancy.

Study Design:

This was an observational study performed in Ealing Hospital, a district general hospital within Greater London. Fifty pregnant women with a Body Mass Index (BMI) >30kg/m2 were asked to complete a questionnaire to assess their knowledge and understanding of obesity during pregnancy, before and after reading a patient educational leaflet. The notes of pregnant women with a BMI >30 kg/m2 were audited against the CMACE/RCOG joint guideline. The feedback from the questionnaire and data from the audit were used to develop a service model to improve the care of obese women in pregnancy.

Results:

60% of women knew the meaning of BMI, but only 32% could recall their own BMI. 72% of women were taking the recommended dose of folic acid. The extensive risks of obesity on fetal and maternal health during pregnancy were largely unknown. Women welcomed an educational leaflet that improved their motivation to make lifestyle changes. We selected 50 sets of patient notes at random to audit; obesity was not recognised as a risk factor in over half the pregnant women with a BMI >30 kg/m2. Height and weight was recorded well but few took the recommended folic acid & Vitamin D. Majority of women were offered GTT and received an appropriate anaesthetic review. There was no documentation of manual handling requirements and little discussion about complications. Blood pressure was measured appropriately in majority of cases but size of cuff was not documented in all.

Conclusion:

There was poor knowledge of obesity effects on pregnancy. An educational leaflet and care pro forma may help achieve standards of healthcare. If the suggested leaflet and pro forma were used, the management of women antenatally should improve.

Keywords

Knowledge

Obesity

Patient Education

Pregnancy

Service Improvement

Introduction

With the prevalence of obesity reaching epidemic proportions, maternal obesity is now one of the most common risk factors in pregnancy. In the United States, around 64% of women of childbearing age are overweight and 35% are obese1, with a similar picture now emerging in Europe2. In the United Kingdom, 50% of maternal deaths are amongst the obese or overweight3 a high proportion of these was attributable to substandard care hence emphasising the need for improving care in obesity. Obesity is a huge burden for the National Health Service (NHS), costing around 0.5 billion pounds per year and a further 2.3 billion pounds in indirect costs for the UK economy4, although the cost of maternal obesity in the United Kingdom has not been shown, studies from France show the cost of prenatal care was higher for women with a BMI >25kg/m2 and even higher for women with a BMI >29kg/m2 because of postnatal care when compared to women of BMI 18 to 24.9 kg/m2 5. The latest CMACE report6 and studies have shown an increased risk of adverse outcomes in pregnancy for this subset of woman; these include subfertility, miscarriage7, Venous Thromboembolism (VTE)8, Pregnancy Induced Hypertension (PIH), Pre-Eclampsia (PET) 9, Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM)10, fetal macrosomia, stillbirths11 and neonatal deaths12. The CMACE/RCOG guidelines13 state that all obese women of child bearing age should be counselled and supported to lose weight pre-pregnancy. Pregnant women with a booking BMI ≥30 kg/m2 should be provided with information on obesity in pregnancy and how risks can be minimised. The CMACE report recommends women with a medical condition that impacts the pregnancy such as obesity, should receive specific pre-pregnancy counselling at every opportunity and prospective management plan. Although such guidelines are present, there is minimal guidance on how women should be given information pre- or during-pregnancy.

To date, there have been many interventional studies which have shown inconclusive evidence14-17 about the range of supportive, educational and behavioural interventions to manage a healthy lifestyle. Studies have shown that advice surrounding healthy weight management during pregnancy is often brief and nonindividualised, more than 80% of women surveyed said general advice from their midwife about weight gain was not good and obesity issues or BMI were not explained18.Although healthcare professionals thought that they were providing gestational weight gain recommendations to overweight/obese women in an effective and empathetic manner, a study19 has shown that there was still a need for more training and access to appropriate tools such as materials and programmes to help with counselling of these women.

We sought to provide tools in the form of written information for patients, care pro forma and a model of service provision to help healthcare professionals to address issues surrounding substandard of care when managing obese women in pregnancy. We addressed this by investigating women’s awareness of obesity associated risks in pregnancy and assessed the potential use of a leaflet to educate patients and provide recommendations of appropriate lifestyle changes. Secondly, we audited pregnancy care for obese women within our department to assess whether standards set by the RCOG/CMACE were being met. Combining the findings of these two studies, we are able to recommend resources to help healthcare professionals provide appropriate care to obese women in pregnancy.

Methods

A questionnaire was designed to assess women’s knowledge of weight control and the effects of obesity during pregnancy (Appendix S1: Questionnaire).

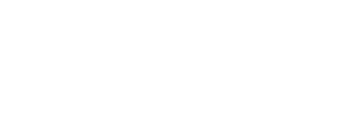

The flow diagram below summarises our questionnaire study:

The questionnaire was distributed to 50 patients with a BMI of >30 kg/m2 attending routine antenatal clinic our obstetrics outpatient department in Ealing Hospital, within Greater London. Participation in the study was voluntary and the women were asked questions by doctors in English or using language interpreters if English was not their first language. Specifically, women were asked if they understood the importance of weight control prior to pregnancy, the meaning of BMI and whether they were aware of their own BMI. They were also asked whether they knew about specific risks of obesity to the mother and baby during pregnancy and childbirth. Women were asked if they had received any information about risks of a raised BMI prior to becoming pregnant and whether they took folic acid supplementation prior to conception.

A leaflet outlining risks of obesity during pregnancy and important lifestyle changes for obese women in pregnancy was designed (Appendix S2: Leaflet) and distributed to the same women. Understanding of the effects of obesity during pregnancy and the acceptance of the leaflet was assessed. Women were asked how motivated they were to making lifestyle changes before and after reading the leaflet, whether they understood the information provided in the leaflet and whether they would benefit from the leaflet.

We audited our care for obese women during pregnancy within our obstetrics department, comparing it to recommendations and standards set out by the CMACE/ RCOG guidelines and local policy (Appendix S3: Pro forma). Data from Euroking, our obstetric database of patient healthcare contacts over a 12 month period was reviewed (January 2014 to January 2015) for women who booked and delivered with a BMI of >30 kg/m2. The delivery type according to BMI was recorded. We also examined 50 sets of notes at random during the same period and reviewed documentation of height and weight, folic acid intake, blood pressure monitoring, discussion of complications, management plan for pregnancy, anaesthetic review, manual handling assessment and infant feeding problems.

Results

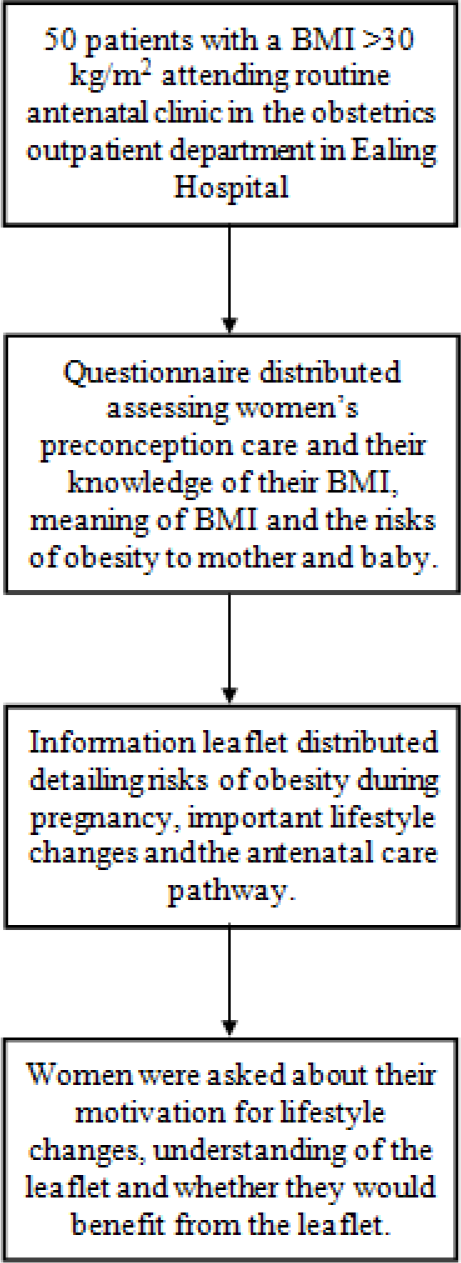

A total of 50 questionnaires were answered voluntarily (response rate 100%). A large proportion (90%, n = 45) of the women knew the importance of weight control before and during pregnancy for a better pregnancy outcome. Although 60% (n = 30) knew what BMI meant, only 32% (n = 16) of women knew what their own BMI was. Figure 1 shows that only 24% (n = 12) of women stated that they were given information on the risks of having a BMI >30 kg/m2. A large proportion of women (72%, n = 36) were taking folic acid and the majority said they were taking the recommended 5 mg dose.

- Results of knowledge of weight control and BMI.

Women were asked whether they knew about specific maternal and fetal associated risks of obesity in pregnancy:

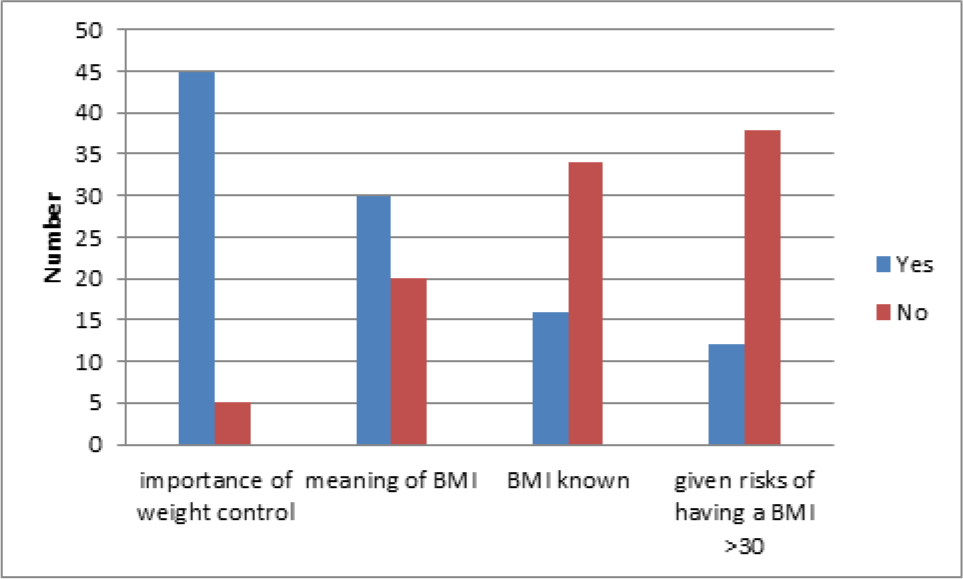

Patient Knowledge of Maternal Risk

Figure 2 shows that the majority of women were aware of an increased risk of diabetes mellitus and high blood pressure in pregnancy, but less knew about the increased risk of Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT), infections, preeclampsia, cardiac disease, post-partum haemorrhage, anaesthetic risks, and wound infections.

- Women's perception of effects of obesity on the mother.

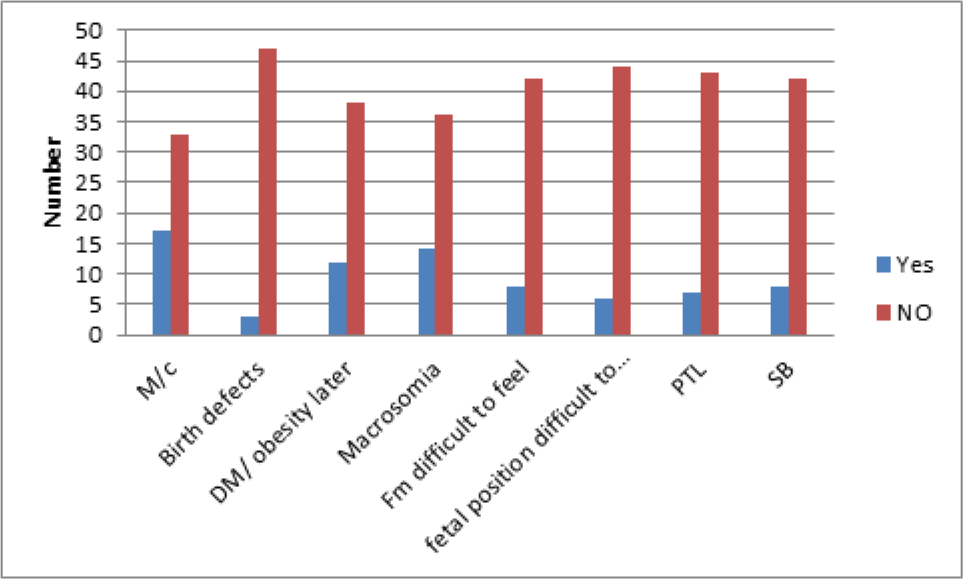

Patient Knowledge of Fetal Risk

Figure 3 shows the knowledge about an increased risk of miscarriage, the child developing diabetes mellitus/ obesity later in life and risk of macrosomia was poor and few knew of the risk of birth defects, increased difficulty in feeling fetal movements, increased difficulty in feeling for fetal position, increased risk of prematurity, and risk of still births and neonatal deaths.

- Understanding of effects of obesity on baby.

Prior to reading the educational leaflet, 18% of women were not at all motivated to make lifestyle changes to control their weight, 48% were slightly motivated, and 34% were very motivated. After reading the educational leaflet, 2% were not at all motivated to make lifestyle changes, 30% were slightly motivated and 68% were very motivated. All of the women recruited in our study understood the leaflet and majority (98%) felt that they could have benefited from the leaflet prior to pregnancy.

Between January 2014 and January 2015, 16% of the women who delivered had a BMI >30 kg/m2 in our department. The mean BMI for these women was 36 kg/ m2.

From the 50 sets of case notes, height and weight was recorded in most cases (96%). However, less than 20% of cases had documentation that information about obesity in pregnancy was provided.

About half of the women in our cohort had a normal vaginal delivery and one sixth had elective caesarean sections and one sixth had emergency caesarean sections. Women with BMI >40 kg/m2 had approximately a 50% caesarean section rate and women with BMI ranging 30-39.9 kg/m2 had approximately a 40% caesarean section rate.

The commonest co-morbidities documented were GDM and PIH (Figure S1). Documentation showed majority of women were taking folic acid, but less than 5% received the recommended 5mg dose. In majority of patients, VTE risk was assessed but there was poor documentation regarding the VTE history and use of anticoagulants in the past. The use of LMWH antenatally was poor and only about half had documented evidence of thromboembolism stockings (TEDS) use.

Blood pressure was measured in more than 80% of patients and at intervals according to guidelines for more than 70% of patients. But the size of cuff was only documented in about 30% of measurements. A glucose tolerance test was offered to more than 80% of patients. A management plan for delivery was documented in 50%, but discussion about complications for delivery was only documented in around 20% of notes and there was little documentation about the difficulties faced when breast feeding. There was no documentation of manual handling requirements.

Of the women with a BMI between 30 and 39.9 kg/m2 less than 5% had an anaesthetic review and about 75% of patients with a BMI >40 had an anaesthetic review.

Discussion

Main findings

The provision of information about risks associated with obesity in pregnancy; pre-conception and in the antenatal period was poor and there was also poor documentation of information provided. Women welcomed written information and counselling regarding specific problems pre-pregnancy and during pregnancy; this may be attained by providing an educational leaflet pre-conceptually, perhaps in primary care, throughout pregnancy and in the postnatal period.

There have been many studies which show that pre-pregnancy obesity and excessive weight gain during pregnancy is associated with complications in pregnancy and obesity in the offspring5,10,20. In our cohort, women’s knowledge about the implications of obesity on the subsequent course of pregnancy was poor, especially so for fetal risks. With the support of written information, such as an educational leaflet, women may be better informed about the risks and management course of their high risk pregnancy. Pregnant women are usually receptive to health care advice and may subsequently be motivated to make lifestyle changes13. Discussion about risks of obesity in pregnancy should be clearly documented for both healthcare providers and patients to refer to and help women achieve attainable goals. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CMACH), now known as CMACE audited the number of women having a BMI > 35kg/m2 and showed the UK prevalence rate of 4.99%3. In our hospital the rate is much higher at 16%; this provides a strong basis for improving care in our unit for obese women in pregnancy.

Our audit of notes showed that height and weight was very well documented (in 96% of patients); this is comparable to finding from the CEMACH project3. This was particularly well documented possibly because the clinical records had a specific area for recording this information. Areas that lacked documentation included the size of blood pressure cuff used, and amount of folic acid and Vitamin D supplementation women were taking. A pro forma was designed and introduced in the maternity notes where information could be clearly documented so that RCOG/CMACE guidelines can be adhered to13. There have been many studies which show improved the quality of documentation with the use of pro formas21-23.

Manual handling was not addressed in any of our patients that were audited, similarly CMACE found that only 14% of notes of BMI >40 kg/m2 had a manual handling assessment. As a part of postnatal care a clear discussion about breast feeding and difficulties in obese women needs to be documented in the notes and a specialist nurse referral needs to be made. Lactation failure resulting in formula fed babies increase the childhood obesity rates24.

We propose developing services with a multidisciplinary approach in-line with planning service provision based on the local population which could mean a separate ‘maternal obesity clinic’. The clinic should include a consultant obstetrician with a special interest in maternal obesity, a midwife a special interest in promoting healthy lifestyle and breast feeding, an anaesthetic specialist with an interest and expertise in technically difficult regional anaesthesia, a dietician, a manual handling expert, and a counsellor for psychological support and breast feeding. Women should be seen either at hospital or out in primary care pre-pregnancy, during pregnancy and after pregnancy to encourage long-term health benefits of diet and exercise to assist this training and education of healthcare workers including those in the primary care setting.

Conclusion

We have shown educational needs of obese women in our local population using a questionnaire; obese women in pregnancy had little knowledge of what effect obesity had upon their own health as well as the health of their unborn child. They welcomed information and help in improving their pregnancy outcome by reducing risk of obesity associated complications. Although there was clear documentation of height and weight in the notes of obese pregnant woman, less than 20% had documentation that information about obesity in pregnancy was provided. There is scope for significant improvement of documentation of VTE history, delivery management plans, manual handling assessments and blood pressure monitoring in this subset of women.

Material and programmes for healthcare professionals and patients improve the management of obese women in pregnancy. Counselling of women should be supported by providing verbal and written information in the form of a leaflet pre-pregnancy and during pregnancy about the risks and how to minimise these. The use of a national pro forma (Appendix S4: National pro forma) may ensure that guidelines in the management of obese women in pregnancy are followed. This may lead to a subsequent reduction in risks and optimisation of appropriate healthcare for this subset of women.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank I. Okaisabor for help with audit data collection and analysis and J. Bhamra for guidance.

Disclosure of Interests

None.

Contributions to Authorship

B. Sagoo designed the leaflet, pro forma, co-ordinated data collection, interviewed patients and wrote the manuscript. KYB Ng designed the questionnaire, interviewed patients and analysed responses. R. Hamid helped approve the leaflet, pro forma, data collection and analysis. All authors helped revise and approve the final manuscript.

Details of Ethics Approval

No ethical approval was required.

Funding

None.

References

- Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999-2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):491-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A nationally representative study of maternal obesity in England, UK: trends in incidence and demographic inequalities in 619 323 births, 1989-2007. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010;34(3):420-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH). Saving mothers' lives: Reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer. The seventh report of the confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom In: CEMACH. 2007.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tackling obesity in England. 2001. Stationery Office. Available from: https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2001/02/0001220.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Weight excess before pregnancy: Complications and cost. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995;19(7):443-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Saving Mothers' Lives: Reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006-2008. The Eighth Report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. BJOG. 2011;118(Suppl 1):1-203.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obesity is associated with increased risk of first trimester and recurrent miscarriage: Matched case-control study. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(7):1644-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maternal smoking, obesity, and risk of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and the puerperium: A population-based nested case-control study. Thromb Res. 2007;120(4):505-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maternal body mass index and the risk of preeclampsia: a systematic overview. Epidemiology. 2003;14(3):368-74.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maternal obesity and pregnancy outcome: a study of 287,213 pregnancies in London. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(8):1175-82.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pre-pregnancy weight and the risk of stillbirth and neonatal death. BJOG. 2005;112(4):403-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maternal obesity and the risk of still birth and neonatal death. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;26(1):S19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Joint Guideline: Management of women with obesity in Pregnancy London. 2010. Available from: https://www.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwii2o23lNXMAhWnK8AKHackAVsQFggiMAA&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.rcog.org.uk%2Fglobalassets%2Fdocuments%2Fguidelines%2Fcmacercogjointguidelinemanagementwomenobesitypregnancya.pdf&usg=AFQjCNGwwb4N3JhVbyXyI82ORwjl-4Nw-cA&sig2=9h7TIc4Fm_n8J420zfzjvg

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of lifestyle intervention on dietary habits, physical activity, and gestational weight gain in obese pregnant women: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(2):373-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Active Mothers Postpartum: A randomized controlled weight-loss intervention trial. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(3):173-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy through dietary and lifestyle counseling: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 Pt 1):305-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weight gain restriction for obese pregnant women: A case-control intervention study. BJOG. 2008;115(1):44-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A Growing Problem. 2010. Does weight matter in pregnancy. Available from: http://cdn.netmums.com/assets/images/2012/A_Growing_Problem_Nov2010.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Obstetric health-care providers' perceptions of communicating gestational weight gain recommendations to overweight/obese pregnant women. Obstet Med. 2012;5(4):161-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maternal obesity and risk for birth defects. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5 Pt 2):1152-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Significant improvement in quality of caesarean section documentation with dedicated operative pro forma-completion of the audit cycle. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;23(4):381-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The surgical admissions proforma: Does it make a difference? Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2015;4(1):53-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Improving documentation and communication using operative note pro formas. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5(1)

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do breast-feeding and delayed introduction of solid foods protect against subsequent obesity? The Journal of Pediatrics. 1981;98(6):883-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Appendix S1

Questionnaire handed out to patients

How much do you know about how your weight affects YOur pregnancy?

If you need any help filling out this leaflet please ask a member of staff

1. Prior to reading the leaflet, did you know that weight control before and during pregnancy is important for a better pregnancy outcome?

Yes [ ] No [ ]

2. Did you know what ‘BMI’ means?

Yes [ ] No [ ]

If yes, please answer question 3. If no, please move to question 4

3. Do you know your BMI?

Yes [ ] No [ ]

4. Did you know about any of the following risks associated with having a BMI of 30 or more?

| Risks to mother | Risks to baby | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | ||

| Diabetes | Miscarriage | ||||

| High blood pressure | Birth defects and congenital anomalies | ||||

| Pre-eclampsia | Diabetes/obesity in later life | ||||

| Cardiac disease | Abnormally large baby | ||||

| Infections | Difficulty in feeling baby kicks | ||||

| Blood clots | Difficulty in feeling baby’s position | ||||

| Bleeding after delivery | Prematurity | ||||

| C-section and instrumental deliveries | Still births and neonatal deaths | ||||

| Anaesthetic risks | |||||

| Wound infection | |||||

5. Were you given any information prior to becoming pregnant on the risks of having a BMI of 30 or more?

Yes [ ] No [ ]

If yes, what kind of information was given and by whom? __________________________________________________________________________________

6. Were you prescribed 5 mg of folic acid prior to pregnancy?

Yes [ ] No [ ]

7. Prior to reading this leaflet, how motivated were you to making healthy lifestyle changes?

Not at all [ ]Slightly motivated [ ]Very motivated [ ]

8. After reading the leaflet, how motivated are you in making healthy lifestyle changes?

Not at all [ ]Slightly motivated [ ]Very motivated [ ]

9. Did you understand the information provided by this leaflet?

Yes [] No []

10. Do you feel that you could have benefited from an information leaflet before pregnancy?

Yes [] No []

Appendix S2

Appendix S3.

OBESITY AUDIT PROFORMA used to collect data from notes

DEMOGRAPHICS

1. Age at Delivery …………………………………………

2. Ethnicity

| White | Mixed | Asian/ Asian british | Black or black brit- ish | Other ethnic group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Irish Other |

White & black car- ribbean White & asian White & black Afri- can Other |

Indian Pakistani Bangla- deshi Other |

Caribbean African Other |

Chinese Other |

3. Deprivation score from postcode……………………………………

4. Marital status:

| Married | Cohabiting | Single | Other | Not known |

5. Previous Miscarraige <24 week:

| 0 | >1 |

6. Previous births (live/still born) ≥ 24 week:

| 0 | >1 |

7. Maternal morbidities:

| Diagnosed prior to this pregnancy | Diagnosed during or after this pregnancy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| GDM | ||||

| T1 DM | ||||

| T2 DM | ||||

| DVT/ PE | ||||

| Es HTN <20 week | ||||

| PIH ≥ 20 week | ||||

| Severe PET (HELLP) / eclampsia | ||||

| CVD | ||||

| Other morbidity | ||||

8. Height ………………………

9. 1st recorded weight ……………………..

10. If not Why no weight:

| No ANC | Weight exceeds scales | Declined to be weighed | Other | Not known |

11. If no weight judged as BMI >35 or weigh >100kg:

| Yes | No |

12. BMI at 1st recorded weight ……………………….

13. Maximum recorded weight during pregnancy…………………………

14. BMI at maximum recorded weight ………………………..

15. Date of delivery……………………………

16. Baby Birth weight……………………………………….

15. Date of delivery……………………………

16. Baby Birth weight……………………………………….

PREPREGNANCY AND EARLY PREGNANCY CARE

Booked at another unit Yes/NO if No:

Gestation at Transfer of care to this unit ………………

Antenatal notes available from maternity unit of booking ……

Folic acid use before or during pregnancy:

| 400mcg | 4mg | 5mg |

| Evidence of informa- tion given antenatal about risk of obesity in pregnancy | YES | NO |

MATERNAL SURVEILLANCE, SCREENING & ASSESSMENT

1. Primary reason for referral to consultant obstetrician…………………

| Yes | NO | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| risk factors identified | |||

| Obesity listed as risk factor | |||

| VTE risk noted at booking | |||

| Previous VTE history | |||

| Evidence of thrombophillia | |||

| Long term warfarin use | |||

| Evidence prophylactic LMWH offered | |||

| Prophylactic LMWH prescribed antenatally | |||

| Evidence of other pharmacological thromboprophylactic agent offered antenatally | |||

| Use of TEDs antenatally | |||

| 1st Antenatal BP measured | |||

| Size of cuff documented | |||

| GTT offered | |||

| Between 24 and 32 week BP and pro- teinuria assessed at least once every 3 weeks | |||

| between 32 week and delivery BP and proteinuria assessed at least once every 2 weeks |

PLANNING LABOUR & DELIVERY

| Yes | NO | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Information given about potential intrapartum complications related to obesity | |||

| Written obstetric management plan for labour & delivery | |||

| If previouys LSCS evidence of risk & benefit of different MOD | |||

| Antenatal anaesthetic consultation | |||

| Assessment to determine manual handling requirements for delivery | |||

| Infant feeding options discussed antenatally |

LABOUR & DELIVERY

| YES | NO | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment of tissue viability | |||

| If operative intervention in theatre evidence that operating staff were alerted about the womans BMI prior to transfer to theatre | |||

| If induced was obesity only indica- tion | |||

| On admission to LW was ST6 above anaesthetist informed about pres- ence | |||

| On admission to LW was ST6 above obstetrician informed about pres- ence | |||

| If operative delivery indicated was ST6 above anaesthetist and obstetri- cian in attendance | |||

| Venous access established prior to delivery | |||

| Use of TEDs during labour & deliv- ery | |||

| If vaginal delivery active manage- ment of 3rd stage recommended | |||

| If LSCS were prophylactic antibiot- ics administered |

After Delivery

| YES | NO | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Evidence that prophylactic LMWH offered postnatal | |||

| Evidence that other pharmacolog- ical thromboprophylactic agent offered postnatal | |||

| Evidence woman received postnatal advice/ support for breastfeeding | |||

| Used of TEDs |

Follow up after pregnancy

| Yes | NO | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Evidence that the woman was offered referral to dietician or nutritionist in the post partum period | |||

| IF GDM documentation for need for a GTT within 2 months following delivery |

Appendix S4

Proposed proforma for the management of Women with

BMI ≥ 30 in Pregnancy

To be put in antenatal notes

| BMI recorded at booking | Please tick | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30.0 - 34.9 (Class I) | ||||||

| 35.0 - 39.9 (Class II) | ||||||

| ≥ 40 (Class III) | ||||||

| ≥ 50 (Super-morbid obesity) | ||||||

| BMI ≥ 30 | BMI sticker on notes | |||||

| Preconception advice received | Yes / No | |||||

| Folic acid 5mg Po od | Date commenced: | |||||

| Vitamin D 25mcg po od | Date commenced: | |||||

| Explain risk factors: Offered Information leaflet Yes/ No Accepted Information leaflet Yes/ No |

Mother Miscarriage Diabetes Pregnancy induced HTN VTE Sleep apnoea Infection IOL/ failed IOL Operative delivery Perineal tear LSCS Unsuccessful VBAC PPH Maternal mortality |

tick | Baby Congenital malformation Macrosomia Misdiagnosis of IUGR Misdiagnosis of fetal lie Still birth Difficult monitoring Shoulder dystocia Birth defects Difficult breast feeding NICU admission Neonatal death |

tick | ||