Translate this page into:

Psychological distress and fear of COVID-19 in cancer patients and normal subjects—A cross-sectional study

*Corresponding author: Dr. Stefania Perna, Department of Scienze e Tecnologie Ambientali, Biologiche e Farmaceutiche, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli,” via Vivaldi 43, Caserta, Italy. stefania.perna@virgilio.it

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Criscuolo MG, Perna S, Hermann A, Stefano CD, Marfe G. Psychological distress and fear of COVID-19 in cancer patients and normal subjects—A cross-sectional study. J Health Sci Res. 2024;9:72-81. doi: 10.25259/JHSR_53_2023

Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study is to evaluate fears, worries, and anxiety among cancer patients and healthy subjects.

Material and Methods

The current study included two study groups (SGs) with 195 respondents, 93 colorectal patients (CCSG-1) and 102 control subjects (CSSG-2). The purpose of this study was to estimate the levels of post-traumatic symptoms, depression, anxiety, and fear of COVID-19 during the pandemic.

Results

In our analysis, we found a slightly higher level of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder in the cancer group than in the control group. Furthermore, we showed no significant difference between the two groups in terms of the impact of fear of COVID-19 infection. Then, we evaluated the relationship among the anxiety, depression and posttraumatic-stress disorder (PTSD) (scales) with the total score fear of COVID-19 scale (FCV-19S) in both groups through a multiple linear regression analysis. We reported that each explicative variable had a moderate influence on the fear of COVID-19 in the cancer group, while in the control group, anxiety and PTSD had a significant influence on the fear of COVID-19 in comparison with depression.

Conclusion

Our results indicate a significant psychological vulnerability in both groups during the strict lockdown. Specifically, we highlight that the control group suffers a negative impact on their mental state. With regard to cancer group, we noted that anxiety, depression, and distress and fear of COVID-19 levels did not increase in significant manner during the pandemic. A possible explanation can be that they are more worried about the delay of their treatment due the COVID-19 emergency. However. more efforts are necessary to better understanding of the mental well-being of the cancer patients and healthy subjects to improve psychological interventions and treatments. during this public health emergency.

Keywords

COVID-19

PTSD

FCV-19S

Colorectal cancer

Patients

INTRODUCTION

After the first report of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) at the end of December 2019, this virus had infected about 560 million individuals around the world by the middle of February 2021.[1,2] On March 17, 2024, data obtained revealed that since the start of the outbreak, 774,954,393 individuals have been diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection globally, and 7,040,264 deaths have been reported by the WHO.[1] (https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c). This pandemic has caused a strong trauma in the general population due to its effect on daily life and relationships, deteriorating the quality of life.[2–4] The physical, emotional and social insecurities and the loss of thousands of lives had a strong impact on mental health, which increased levels of stress, anxiety and depression in the medium and long term. During the pandemic, many cases of the coexistence of cancer and SARS-CoV-2 infection were described by preliminary studies. In this regard, Liang et al. (2020)[5] observed that the rate of COVID-19 infection among cancer patients was higher than in the general population. In addition, in a retrospective study on cancer patients with infection, Zhang et al. (2020)[6] showed a high susceptibility to infection in these patients. As demonstrated by Lee et al. (2021)[7] in a large trial with more than 20,000 cancer patients, there was a significant risk of COVID-19 infection among cancer patients, specially in older and male patients. In this context, several studies have reported an increase in mental health symptoms (e.g., anxiety, depression, distress, post-traumatic stress disorder) among cancer patients.[3,8–11] Specifically, Ng et al. (2020)[10] observed that 66% of cancer patients had a high level of fear of COVID-19. Furthermore, at the beginning of the pandemic, the results of qualitative studies showed that cancer patients were exposed to high fears about potential infection when they received health care.[12] In this regard, psychological distress can increase along with worsening symptoms and poor quality of life in cancer patients.[13] In addition, these patients experienced a very anxious period due to several reasons, such as other concomitant diseases, taking immunosuppressive treatment, increased risk of infection, postponing surgical interventions, switching health service personnel to other areas, or absence of a health provider, not being able to use systems such as telemedicine exclusively.[14] Moreover, restrictions due to the pandemic caused a sudden change in the normal population’s habits with an increase in mental health distress, as reported by different studies.[15,16] Brooks et al. (2020)[17] studied the psychological effects of quarantine during the pandemic, indicating the psychological burden on individuals who are unable to participate in public life. Threatening events or extraordinary situations, such as the pandemic can trigger emotional states like fear.[18] In these cases, fear works as a defense mechanism, but if excessive, it can cause increased anxiety that in turn, can negatively impact both the symptoms of cancer and the effect of therapy.[19,20] Furthermore, some measures, such as delays in surgeries and chemotherapy treatments, hospital bed shortages, online appointments, and the prescription of oral antineoplastic drugs, have increased levels of distress and fear in patients during their chemotherapy treatment.[21,22] In this context, we carried out a cross-sectional study of the psychological status of outpatients with colorectal cancer (CRC) and healthy people during lockdown at our non-COVID Cancer Center Institute in southern Italy. The goals of our study were: (i) to measure the levels of post-traumatic symptoms, depression, and anxiety during the pandemic in the cancer and control group and (ii) to investigate the fear of COVID-19 infection by using the FCV-19S in both groups.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Recruitment and Data Collection

The study was conducted from February 12 to the end of April 2020, during the strict lockdown measures in Italy. The population of the study consisted of two study groups: 93 colorectal cancer patients, colorectal cancer study group 1 (CCSG-1) who attended our oncology outpatient before the lockdown and 102 control subjects, control subject, study group-2 (CSSG-2). Ninety-three cancer patients (48 females and 45 males) and 102 normal subjects (57 females and 45 males) aged 18 and over were recruited and able to use social networks and volunteers to participate in the study. Data were collected via online survey systems due to the ongoing pandemic during the study period, and no face-to-face interviews were conducted to collect data. Impact of event scale-revised (IES-R), the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS), and the fear of COVID-19 scale (FCV-19S), were used for data collection. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli (Prot. Number 297).” Informed consent was obtained online from all individual participants in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, included in this study.

Instruments

A brief questionnaire was administered online to all participants, cancer patients and normal subjects, which consisted of two parts: the first, asking general information about the age, sex, education level and marital status, and job. Furthermore, clinical data that include the date of primary cancer diagnosis, tumor location, stage at diagnosis, primary treatment received, and time since diagnosis were obtained through linkage with the Oncology Department. The control population was matched to the colorectal cancer (CRC) population based on a frequency distribution over age and sex strata to maximize the number of both groups. Then, the impact of event scale-revised (IES-R)[23] and the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS)[24,25] were administered to all participants. The first questionnaire measures a person’s subjective reaction after a traumatic event, leading to the diagnosis of posttraumatic-stress disorder (PTSD). The IES-R is composed of 22 items divided into three subscales measuring avoidance, intrusion, and hyperarousal. Answers ranged on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). The second questionnaire has been developed to estimate the state of anxiety and depression in non-psychiatric patients with organic disease. The HADS is composed of 14 items, seven of which measure anxiety (HADS-Anxiety, HADS-A) and the other seven measure depression (HADS Depression, HADS-D) on a four-point Likert scale. The scale has demonstrated satisfactory psychometric characteristics in both cancer patients and normal subjects, and, in addition, it has been translated and validated in the Italian population.[24,25] Furthermore, the test of FCV-19S was used by considering that of Ahorsu et al. (2022)[26] (developed in 2022 and translated into an Italian version). According to Ahorsu et al. (2022),[26,27] the response for each item was recorded according to a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), allowing respondents to express their level of agreement concerning the psychological object surveyed. All questionnaires were sent to all subjects online and then collected. Besides, this study was conducted on a voluntary basis for all participants and without incentives.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics, including means and central tendency measures, were used to explore sample populations and item characteristics. The PTSD according to gender, age, education, employment, anxiety, and depression were analyzed by the Chi-square method in both groups. To explore the relationship between the Fear of COVID-19 and PTSD, Anxiety and Depression scales, correlation analyses (Pearson correlation) were performed in both groups. Moreover, a linear multiple regression test was used to analyze the dependence of FCV-19S on the following variables: gender, age, education, employment PTSD, anxiety and depression in both groups. Statistical analysis was carried out using IBM SPSS (Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) and GraphPad Prism software version 6.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA).

RESULTS

Socio-demographic characteristics of colorectal cancer patients and normal subjects

The participants of both groups filled out a brief socio-demographic questionnaire. The mean age scores of cancer and control groups were 53 years (S.D. 9.41; range = 30–81) and 50 years (S.D. 11.16; range = 33–77), respectively. In addition, in both groups, there were more females (48 cancer pts 51.61%; 57 healthy subjects, 55.8%) than males (45 cancer patients, 48.38%; 45 healthy subjects, 44.11%), respectively. 63.44% of cancer patients were employed, and 36.55% were not employed, while in the control group, 50.98% of participants were employed, and 49.01% were not employed. Furthermore, in group 1 (cancer patients) 37.63% had low education, and 62.36% had high education, while in group 2 (healthy subjects) 34.31% had low education, while 65.68% had high education. Most patients were diagnosed with early-stage colorectal cancer (I, II 63.43%), while 35.55% of patients were diagnosed with third-stage colon cancer. In addition, they had received surgical (4.30%), surgical/chemotherapy (58.05%) or chemotherapy (37.63%) treatment. Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of all the participants are reported in Table 1. No statistically significant difference was detected between the two groups in terms of marital status, education, and employment.

| Characteristic | Cancer Patients (Group 1) | Control Group (Group 2) |

|---|---|---|

| Age/years | Age/years | Age/years |

| Mean | 53.82 | 50.13 |

| S.D. | 9.41; | 11.16 |

| 30-50 (range) | 35 (37.63%) | 59 (57.84%) |

| 50-70 (range | 58 (62.35%) | 43 (42.15%) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 48 (51.61) | 57 (55.80%) |

| Male | 45 (48.38%) | 45 ( 44.11%) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Unmarried | 47 (50.53%) | 48 (27.05%) |

| Married | 39 (41.93%) | 41 (40.10%) |

| Divorced | 7 (7.5%) | 13 (12.74%) |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 35 (37.63% | 35 (34.31%) |

| High school and above | 58 (62.36%) | 67 (65.68%) |

| Employment | ||

| Yes | 59 (63.44%) | 52 (50.98%) |

| No | 34 (36.55%) | 50/49.02 |

|

Cancer type Colon Rectum |

93 (100%) | |

| Tumor stage at diagnosis | ||

| Stage I | 6 (6.45%) | |

| Stage II | 53 (56.98%) | |

| Stage III | 34 (35.55%) | |

| Current Treatment | ||

| Surgery | 4 (4.30%) | |

| Surgery+Chemoterapy | 54 (58.06%) | |

| Chemotherapy | 35 (37.63%) |

SD: standard deviation.

Levels of the HADS in both colon cancer patients and normal subjects

In the analysis of HADS-General Scale score (HADS-GEN) in Group 1, the mean score was 16.65 (SD ± 3.97). We observed that 78.49% of patients (n = 73), were above the cut-off (score 13), while 21.50% (n = 20) were in the range (score 9–13) for the general scale. Specifically, we found that 64.51% (n = 60) of cancer patients were above the cut-off range (score 8) for HADS-A scale and 61.29% (n = 57) were above the cut-off range (score 8) for HADS-D scale [Table 2]. In the control group, we found that the mean HADS-General Scale score (HADS-GEN) was 14.83 (SD ± 5.35) and 59.80% of the respondents (n = 61) were above the cut-off (score ≥ 13), while 40.19% (n = 41) were in the range (score 9–13) for the general scale. Meanwhile, 49.01% (n = 50) of control respondents were above the cut-off range (score: 8) for HADS-A scale and 50.97% (n = 52) were above the cut-off range (score: 8) for HADS-D scale [Table 2]. The Chi-Square test for HADS-General scale’s mean between cancer and normal groups was significant at 5% [Table 3].

| HADS Gen | Mean (±SD) | N (93) | % (100) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (CPs) | 16.65 (±3.97) | ||

| Score range (9–13) | 20 | 21.50 | |

| Score >13 | 73 | 78.49 | |

| N (102) | % (100) | ||

| Group 2 (NSs) | 14.83 (±5.35) | ||

| Score range (9–13) | 41 | 40.19 | |

| Score >13 | 61 | 59.80 | |

| HADS-A | |||

| Group 1 (CPs) | N (93) | % (100) | |

| 8.32 (±2.37) | |||

| Score range (0–7) | 33 | 35.48 | |

| Score range (8–10) | 43 | 46.23 | |

| Score range 11–21) | 17 | 18.27 | |

| Group 2 (HSs) | N (102) | % (100) | |

| 7.28 (±2.66) | |||

| Score range (0–7) | 52 | 50.90 | |

| Score range (8–10) | 41 | 40.19 | |

| Score range (11–21) | 9 | 8.82 | |

| HADS-D | |||

| Group 1 (CPs) | N (93) | % (100) | |

| 8.39 (±2.32) | |||

| Score range (0–7) | 36 | 38.70 | |

| Score range (8–10) | 48 | 51.61 | |

| Score range (11–21) | 9 | 9.67 | |

| Group 2 (HSs) | N (102) | % (100) | |

| 7.44 (±3.01) | |||

| Score range (0–7) | 50 | 49.01 | |

| Score range (8–10) | 43 | 42.15 | |

| Score range (11–21) | 9 | 8.82 | |

| ISE-R | |||

| Group 1 (CPs) | N (93) | % (100) | |

| 39.80 (±11.75) | |||

| Score (<24) no diagnosis of PTSD | 9 | 9.67 | |

| Score range (24–33) Mild PTSD | 22 | 23.65 | |

|

Score range (33–37) Moderate PTSD |

15 | 16.12 | |

|

Score (>37) Severe PTSD |

47 | 50.53 | |

| IES-R Intrusion | 14.25 (±5.03) | ||

| IES-R Avoidance | 14.64 (±3.60) | ||

| IES-R Hyperarousal | 10.77 (±4.07) | ||

| Group 2 (HSs) | N (102) | % (100) | |

| 35.17 (±11.27) | |||

| Score (<24) no diagnosis of PTSD | 31 | 30.39 | |

| Score range (24–33) Mild PTSD | 11 | 10.78 | |

|

Score range (33–37) Moderate PTSD |

14 | 13.72 | |

|

Score (>37) Severe PTSD |

46 | 45.09 | |

| IES-R Intrusion | 13.30(±4.68) | ||

| IES-R Avoidance | 12.94 (±3.72) | ||

| IES-R Hyperarousal | 9.01 (±3.45) |

PTSD: Posttraumatic-stress disorder, CPs: Cancer patients, HS: Healthy subjects, HADS-A: Hospital anxiety and depression scale-anxiety, HADS-D: Hospital anxiety and depression scale-depression, IES-R: Impact of event scale-revised, N: number of patients, SD: Standard deviation.

| Colorectal cancer patients | Control Group | χ2 | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HADS Gen | 16.65 (±3.97) | 14.83 (±5.35) | 4.827 | 0.0280* |

| ISE-R | 39.80 (±11.75) | 35.17 (±11.27) | 13.44 | 0.0003*** |

HADS-D: Hospital anxiety and depression scale-depression, IES-R: Impact of event scale-revised.

*P ≤ 0.05

***P ≤ 0.001

Levels of the IES-R in cancer patients and normal subjects

In the cancer group, the mean IES-R score of patients was 39.80 (SD ± 1175), and in addition, 9.67% of them (n = 9) did not show a PTSD diagnosis (score range < 24) while. 23.65% (n = 22, score range: 23–33), had mild PTSD. Furthermore, 16.12% (n = 15) and 50.5% (n = 47) had moderate (score range 33–37) and severe levels (score >37), respectively [Table 2]. Mean scores for the IES-R subscales were: avoidance 14.64 (SD ± 3.60), intrusion 14.25 (SD ± 5.03), and hyperarousal 10.77 (SD ± 4.06) [Table 2]. In the control group (Group 2), the mean IES-R score of these respondents was 35.17 (SD ± 11.27). In these participants, 30.39% (n = 31) of them did not show a PTSD diagnosis (score <24), while 10.78% (n = 11, score range: 23–33) had mild PTSD. Moreover, 13.72% (n = 14) and the 45.09% (n = 46) had a moderate (score range 33–36) and a severe level (score >37) for PTSD, respectively. Mean scores for the IES-R subscales were: avoidance 12.94 (SD ± 3.72), intrusion 13.30 (SD ± 4.68), and hyperarousal 9.01 (SD ± 3.45) [Table 2]. In this case, the Chi-Square test was highly significant at 1% between the two groups [Table 3].

Fear of COVID-19 on traumatic distress in cancer patients and normal subjects

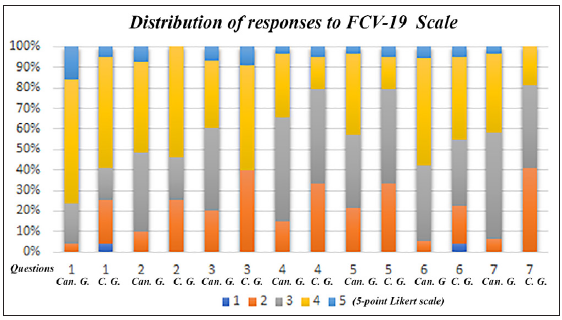

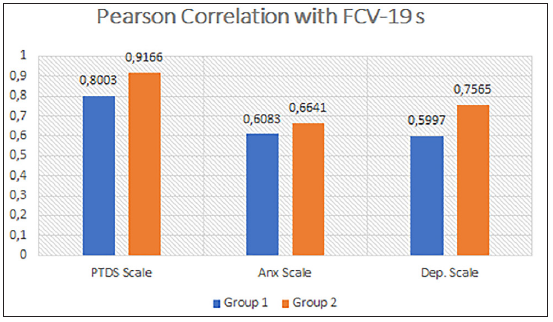

This study that used the FCV-19S showed that 16.12% of cancer patients and only 4.9% of the control group reported that they strongly agreed with the statement: “I am very afraid of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.” The second option, “agree” was chosen by 60.12% of cancer patients and 53.92% of control respondents, respectively. In the second question on feelings of anxiety at the thought of the virus, 7.52% and 44.08% of cancer patients reported to strongly agree or agree on this topic, respectively. In the control group, 53.92% of respondents reported to agree on their feelings on the virus. The statement “My hands become clammy when I think of coronavirus” was disagreed with in 20.43% of oncology patients and almost the same percentage in the control group (21.56%). Moreover, 34.4% (agree 31.18% and 3.22% strongly agree) of cancer patients reported that they were afraid to lose their life and, while 20.58% (agree 15.68 and strongly agree 4.90%) of normal respondents were afraid of losing their lives due to the virus. A greater impact of pandemic information from social media was observed in both groups. In this regard, 43% of cancer patients agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, “When I watch the news and learn about coronavirus-related stories on social media, I get nervous or feel anxious,” compared with 20.58% of normal respondents. Then, 58.05% of patients agreed (52.68) or strongly agreed (5.37) with the statement that they could not sleep for fear of SARS-CoV-2 infection, whereas in the control group, 45.09% people marked this response (agreed 40.19% or strongly agreed 4.90%). At the end, the last statement of the questionnaire was, “My heart beats rapidly when I think of a coronavirus infection.” In this regard, 38.70% of the cancer patients agreed with this statement, along with 18.62% of the control group [Table 4 and Figure 1]. In addition, we noted no significant difference between the two groups in terms of the impact of fear of COVID-19 infection [Table 4 and Figure 1]. Next, to better understand the impact of fear of COVID-19 infection in both groups, we analyzed the correlations (Pearson analysis) between the constructs considered in the study. In group 1 (cancer patients), there was a positive correlation between FCV19 scale and PTSD scale (r = 0.8003, p = 0.0001), while there was a slightly lower correlation between FCV19 scale and Anxiety scale (r = 0.6087, p = 0.0001) and FCV19 scale and depression scale (r = 0.5997, p = 0.0001) [Table 5 and Figure 2], while in group 2 (control group) there was a high significant correlation between FCV19 scale and PTSD scale (r = 0.9166, p = 0.0001), while there was a slightly lower correlation between FCV19 scale and Anxiety scale (r = 0.6641, p = 0.0001) and FCV19 scale and Depression scale (r = 0.7565, p = 0.0001) [Table 5 and Figure 2]. Based on these correlations, further investigation highlighted the factors affecting Fear of COVID-19, PTSD, Anxiety and Depression in both groups. The stepwise model selection in multiple linear regression analysis, which considered FCV19 as a dependent variable, is presented in Table 6. The model had R2 = 0.83 (adjusted R2 = 0.70) which means that 70% of the variance in the FCV19 is explained by the model. In the cancer group, PTSD seems to be the lowest predictor (b = 0.20 p < 0.001), while Anx (b = 0.30, p < 0.01) and the Dep (b = 0.33, p < 0.013) were moderate predictors. Furthermore, in the control group, the model had R2 = 0.93 (adjusted R2 = 0.86) which means that 86% of the variance in the FCV19 scale is explained by the model. PTSD (b = 0.472, p < 0.001), Anxiety (b = 0.497 p < 0.01) seem to be more significant predictors when compared to Depression (b = –0.530, p < 0.01) [Table 6].

| Items | Groups | N. tot (%)Strongly Disagree1 | N. tot (%)Disagree2 | N. tot (%)Neutral3 | N. tot (%)Agree4 | N. tot (%)Strongly Agree5 | Total | Mean (±SD) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

QF.1 I am most afraid of Corona |

Cancer Group (1) Control Group (2) |

0 (0%) 4 (3.92%) |

4 (4.30%) 22 (21.56%) |

18 (19.35%) 16 (15.68%) |

56 (60.21%) 55 (53.92%) |

15 (16.12%) 5 (4.90%) |

93 (100%) 102 (100%) |

3.88 (±0.72) 3.34 (±0.95) |

0.1723 |

|

QF.2 It makes me uncomfortable to think about Corona |

Cancer Group (1) Control Group (2) |

0 (0%) 0 (0%) |

9 (9.67%) 26 (25.49%) |

36 (38.70) 21 (20.58) |

41 (44.08%) 55(53.92%) |

7 (7.52%) 0 (0%) |

93 (100%) 102 (100%) |

3.49 (±0.77) 3.28 (±0.84) |

0.5731 |

|

QF.3 My hands become clammy when I think about Corona |

Cancer Group (1) Control Group (2) |

0 (0%) 0 (0%) |

19 (20.43%) 22 (21.56%) |

37 (39.76%) 47 (46.07%) |

31 (33.33%) 28 (27.45%) |

6 (6.45%) 5 (4.90%) |

93 (100%) 102 (100%) |

3.25 (±0.85) 3.15 (±0.81) |

0.7941 |

|

QF.4 I am afraid of losing my life because of Corona |

Cancer Group (1) Control Group |

0 (0%) 0 (0%) |

14 (15.05%) 34 (33.33%) |

47 (50.53%) 47 (46.07%) |

29 (31.18%) 16 (15.68%) |

3 (3.22%) 5 (4.90%) |

93 (100%) 102 (100%) |

3.22 (±0.73) 2.92 (±0.82) |

0.4068 |

|

QF.5 When I watch news and stories about Corona on social media, I become nervous or anxious. |

Cancer Group (1) Control Group (2) |

0 (0%) 0 (0%) |

20 (21.50%) 34 (33.33 |

33 (35.48%) 47 (46.07%) |

37 (39.78%) 16 (15.68%) |

3 (3.22%) 5 (4.90%) |

93 (100%) 102 (100%) |

3.24 (±0.82) 2.94 (±0.94) |

0.4089 |

|

QF.6 I cannot sleep because I’m worrying about getting Corona. |

Cancer Group (1) Control Group (2) |

0 (0%) 4 (3.92%) |

5 (5.37%) 19 (18.62%) |

34 (36.55%) 33 (32.35%) |

49 (52.68%) 41 (40.19%) |

5 (5.37%) 5 (4.90%) |

93 (100%) 102 (100%) |

3.58 (±0.68) 3.23 (±0.94) |

03533 |

|

QF.7 My heart races or palpitates when I think about getting Corona. |

Cancer Group (1) Control Group (2) |

0 (0%) 0 (0%) |

6 (6.45%) 42 (41.17%) |

48 (51.61%) 41 (40.19%) |

36 (38.70%) 19 (18.62%) |

3 (3.22%) 0 (0%) |

93 (100%) 102 (100%) |

3.38 (±0.65) 2.77 (±0.74) |

0.0974 |

FCV-19S Fear of COVID-19 scale, N: Number of cancer patients percentage (%) and mean±standard deviation (SD), P-value = Chi-Square test, QF: Question fear.

- Distribution of responses on Fear of COVID-19 items between Cancer Group (1) and Control Group (2).

| Groups | Pearson’ Corrrelation | r | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Cancer Group (1) Control Group (2) |

FCV-19s vs PTSD scale FCV-19 S vs PTSD scale |

0.8003 0.9166 |

p = 0.0001*** p = 0.0001*** |

|

Cancer Group (1) Control Group (2) |

FCV-19s vs Anxiety S FCV-19s vs Anxiety scale |

0.6083 0.6641 |

p = 0.0001*** p = 0.0001*** |

|

Cancer Group (1) Control Group (2) |

FCV-19s vr Depression scale FCV-19s vr Depression scale |

0.5997 0.7565 |

p = 0.0001*** p = 0.0001*** |

- Pearson correlations between Fear of Covid-19 (FCV-19 scale) and posttraumatic-stress disorder (PTSD) scale, FCV-19 scale and anxiety scale, and FCV-19 scale and depression scale in Cancer Group (1) and Control Group (2).

| Group 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | B | SE | Beta | t | R 2 |

| 0.70 | |||||

| PTSD | 0.200 | 0.025 | 0.596 | 7.924 | |

| A | 0.304 | 0.120 | 0.183 | 2.522 | |

| D | 0.337 | 0.128 | 0.188 | 2.269 | |

| Group 2 | |||||

| Variables | SE | Beta | t | R 2 | |

| 0.86 | |||||

| PTSD | 0.472 | 0.032 | 1.010 | 14.70 | |

| A | 0.497 | 0.119 | 0.252 | 4.180 | |

| D | –0.530 | 0.149 | –0.304 | 3.557 |

PTSD: Posttraumatic-stress disorder, A: Anxiety, D: Depression, B: unstandardized beta, SE: Standard error, t-value in logistic regression, R2: R-squared.

DISCUSSION

During the pandemic, the Italian population faced a dramatic situation due to a forced lockdown. This situation, as shown by the data of our study, negatively influenced its inhabitants. Here, we analyzed the psychological status of cancer patients and healthy people through the administration of validated questionnaires to estimate their Anxiety, Depression, PTSD. In this regard, we built a procedural sample including most patients with colorectal cancer at stages I and II and a small percentage of patients at stage III, in order to better estimate and compare their fear of the virus during the pandemic. Data collected online in cancer patient samples reported that 64.50% of them were above the cut-off range (score 8) for HADS-A scale and 61.28% were above the cut-off range (score 8) for HADS-D scale. Meanwhile, in the control group, 49.01% of control respondents were above the cut-off range (score: 8) for HADS-A scale and 50.97% were above the cut-off range (score: 8) for HADS-D scale. Furthermore, we noted that 9.67% of cancer patients did not show a PTSD diagnosis (score range < 24), while 23.65% had mild PTSD. In addition, 16.12% and 50.53% of them had moderate (score range 33–37) and severe levels (score > 37), respectively. In the control group (Group 2), 30.39% of them did not show a PTSD diagnosis (score <24), while 10.78% (score range: 24–33) had mild PTSD. Moreover, 13.72% and 45.09% of them had a moderate (score range 33–36) and a severe level (score >37) for PTSD, respectively. Moreover, we observed a minimal difference in HADS General scale and a moderate difference in PTSD scale when we compared the cancer and control groups. The number of studies that evaluated and compared anxiety, depression and PTSD levels in oncological patients during the pandemic had different outcomes. For example, among ovarian cancer patients receiving treatment or who had ended it, HADS levels were comparable with other previously published results.[28] In another study, Rodrigues-Oliveira et al. (2022)[29] observed that the anxiety, depression, and PTSD levels in head and neck cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy did not increase during the pandemic. In contrast, breast cancer patients and survivors presented significant levels of anxiety and depression symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic when compared with other published data.[30] Our study reported that the estimated anxiety, depression and PTSD levels had a moderate difference from those of the control group. In this regard, in the case of cancer patients the level of anxiety, depression and PTSD could increase and then, be associated with the fact that during the pandemic they can be considered very vulnerable due to the biological and psychological burdens of their disease.[30,31] Besides, in the normal participants, the psychological effects during the pandemic had a significant impact as shown by the high level of Anxiety and PTSD. Our results agreed with previous Italian studies that showed how COVID-19 pandemic and strict lockdown had a negative effect on its citizens. In particular, the data underlined the significant impact on anxiety and depression in both men and women.[32,33] Furthermore, in another study from Spain, the authors reported elevated anxiety levels following COVID-19 news.[34] In this regard, the growing threat of the pandemic around the world, as well as social isolation and the overload of media information have led to additional distress, generating a vicious cycle. Naturally, these methods and the pandemic itself often disrupt psychosocial life, thereby creating a sense of approaching fear, which may cause mental problems.[35–38] Furthermore, we noted no statistically significant difference in favor of colorectal cancer patients, as compared to the control group, regarding the level of fear of COVID-19 infection. In this context, we performed a Pearson correlation to better investigate how anxiety, depression and PTSD could affect the fear of COVID-19 in both groups. In line with the literature,[39,40] our results confirmed the strict relationship between PTSD and FCV-19 in both groups. Interestingly, we observed a lower association between PTSD and FCV-19 (r = 0.8003, p = 0.0001) in the cancer patient group than in the control group (r = 0.9166, p = 0.0001), as also shown in another paper by Musche et al. 2020.[41] In this study, Musche et al. (2020)[41] reported that levels of distress or fear related to COVID-19 in cancer patients were lower than healthy controls This result might be explained by the fact that cancer patients had more details on virus to prevent infection than normal individuals. Furthermore, it is possible that the experience of being diagnosed with cancer acts as a psychological protective factor, and additionally, cancer patients needed a constant monitoring through telemedicine during the pandemic with adequate psychological support.[42] Furthermore, we investigated the relationship among the levels of Anxiety, Depression and PTSD in cancer patients and healthy subjects with the total score of the FCV-19 scale through a multiple linear regression analysis. We found that each explicative variable had a moderate influence on the Fear of COVID-19 in the cancer group, while in control group, Anxiety and PTSD had a significant influence on the fear of COVID-19 in comparison with depression, as shown by other studies.[40,43–49] Specifically, we found that the fear of COVID-19 infection was influenced by higher levels of PTSD and Anxiety in the control group than in cancer patients. This could be due to different reasons. First, there is an increase in insecurity and/or the fear of losing loved ones. Furthermore, the fear of getting infected could lead to a destructive psychological burden, with high mental disorders, weakening the immune system and reducing the body’s ability to fight disease in people. Moreover, cancer patients are more able to cope with the infection than the normal participants because they are more resilient and in addition, they believed that their cancer treatment was more important than the risk of having the infection and severe complications. One study showed that resilience was often correlated with mental well-being.[48] In another study, Seiler and Jenewein (2019)[49] found that resilience worked as a protective factor against psychological distress. Moreover, resilience has been found to be associated with personal factors such as optimism,[50,51] self-esteem and self-efficacy.[52] In other words, a person can utilize personal resources to steer toward a certain outcome.[53–55] In this context, resilience can improve personal strength to confront future events, a phenomenon referred to as post-traumatic growth.[56,57] In summary, our study confirms the need to address the potential long-term consequences of COVID-19 for the mental health of cancer patients and normal people.

CONCLUSION

In this scenario, further investigations should involve longitudinal studies exploring the long-term effects of the virus outbreak and lockdown on cancer patients and normal population in order to discover the ways in which COVID-19 has permanently affected the psychological functioning of these populations. Moreover, new developments could focus on examining other anxiety-related conditions resulting from the pandemic, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder or social anxiety. Further research would allow a better understanding of the mental well-being of these populations and improve psychological interventions and treatments.

Data availability

The author confirms that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Material. Row data that support the finding of this study available from corresponding author, upon reasonable request

Author contributions

MGC and GM conceived and planned the project. GM, CDS, SP and AH participated in study design in development of methods for data collection and analysis. All authors contributed to the refinement of the study protocol and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli (Prot. Number 297)

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Assisted Technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. [accessed 2022 May 13]. https://covid19.who.int

- Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A clinical update. Front Med. 2020;14:126-35.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluating mental health-related symptoms among cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic: An analysis of the COVID impact survey. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;17:e1258-e1269.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Projected increases in suicide in Canada as a consequence of COVID-19. Psychiatry Research. 2020;294:113492.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: A nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical characteristics of COVID-19-infected cancer patients: A retrospective case study in three hospitals within Wuhan. China Ann Oncol. 2020;31:894-90.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- COPE consortium. Cancer and Risk of COVID-19 through a general community survey. Oncologist. 2021;26:182-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Examining the association among fear of COVID-19, psychological distress, and delays in cancer care. Cancer Med. 2021;10:8854-65.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Distress and spiritual well-being in brazilian patients initiating chemotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic-A cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:13200.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological distress during the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic among cancer survivors and healthy controls. Psychooncology. 2020;29:1380-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of mental health problems among patients with cancer during COVID-19 pandemic. Trans Psychiatry. 2020;10:263.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Patient perspectives on chemotherapy de-escalation in breast cancer. Cancer Med. 2021;10:3288-98.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Adjusting to life after treatment: Distress and quality of life following treatment for breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:1625-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Health-related quality of life and experiences of sarcoma patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:2288.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Changes in self-reported health, alcohol consumption, and sleep quality during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Appl Econ Lett. 2022;29:219-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Associations between changes in daily behaviors and self-reported feelings of depression and anxiety about the COVID-19 pandemic among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2022;77:e150-e159.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912-20.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Effectiveness of nursing intervention to control fear in patients scheduled for surgery. Revista de la Facultad de Medicina. 2018;66:195-200.

- [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances in COVID-19 patients: A meta-analysis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2021;1486:90-111.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of progressive muscle relaxation on anxiety and sleep quality in patients with COVID-19. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2020;39:101132.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on care of oncological patients: Experience of a cancer center in a latin American pandemic epicenter. Einstein (Sao Paulo). 2020;19:eAO6282.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological distress in outpatients with lymphoma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1270.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The impact of event scale-revised. In: Wilson J. P., Keane T. M., eds. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. New York: The Guilford Press; 1997. p. :399-411.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychometric properties of the impact of event scale - Revised. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:1489-96.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1983;67:361-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The fear of COVID-19 scale: Development and initial validation. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2022;20:1537-45.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Detecting psychological distress in cancer patients: Validity of the Italian version of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. Support Care Cancer. 1999;7:121-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on the quality of life for women with ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:725.e1-725.e9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 impact on anxiety and depression in head and neck cancer patients: A cross-sectional study. Oral Dis. 2022;28:2391-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient-reported outcomes of patients with breast cancer during the COVID-19 outbreak in the epicenter of china: A cross-sectional survey study. Clin Breast Cancer. 2020;20:e651-e662.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Understanding the factors related to trauma-induced stress in cancer patients: A national study of 17 cancer centers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:7600.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Cognitive and mental health changes and their vulnerability factors related to COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. PLoS One. 2021;6:e0246204.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological impact of the lockdown in italy due to the COVID-19 outbreak: Are there gender differences? Front Psychol. 2021;12:567470.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Coping behaviors associated with decreased anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:80-1.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Mental health outcomes of the COViD‐19 pandemic. Riv Psichiatr. 2020;55:137‐44.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The psychology of pandemics: Preparing for the next global outbreak of infectious disease. Cambridge Scholars Publishing; 2019.

- The outbreak of COVID‐19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66:317‐20.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on mental health and quality of life among local residents in Liaoning Province, China: A cross‐sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:e2381.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of fear of COVID-19 infection on functionality in breast cancer patients in the pandemic Iranian. Red Crescent Medical Journal. 2022;24

- [Google Scholar]

- The association between fear of COVID-19 and health-related quality of life: A cross-sectional study in the greek general population. J Pers Med. 2022;12:1891.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19-related fear and health-related safety behavior in oncological patients. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1984.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Panel members. Managing cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: An ESMO multidisciplinary expert consensus. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:1320-35.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The relationship between quality of life and fear of Turkish individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2021;35:472-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of fear of COVID-19 on mental well-being and quality of life among saudi adults: A path analysis. Saudi J Med Sci. 2021;9:24-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Fear and death anxiety in the shadow of COVID-19 among the lebanese population: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0270567.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life in the COVID-19 pandemic in India: Exploring the role of individual and group variables. Community Ment Health J. 2021;57:70-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Validation and psychometric evaluation of the italian version of the fear of COVID-19 scale. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2022;20:1913-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The association between resilience and mental health in the somatically Ill. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115:621-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Resilience in cancer patients. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:208.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life and personal resilience in the first two years after breast cancer diagnosis: Systematic integrative review. Br J Nurs. 2019;28:S4-S14.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resilience and associated factors among chinese patients diagnosed with oral cancer. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:447.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Resilience in koreans with cancer: Scoping review. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2019;21:358-64.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Development of a new resilience scale: The connor-davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC) Depress Anxiety. 2003;18:76-82.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towards a transversal definition of psychological resilience: A literature review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55:745.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Resilience as a multimodal dynamic process. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019;13:725-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interventions to promote resilience in cancer patients. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;51-52:865-72.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of an empowerment program on resilience and posttraumatic growth levels of cancer survivors: A randomized controlled feasibility trial. Cancer Nurs. 2019;42:E1-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]